The Man, The Legend, and His Music

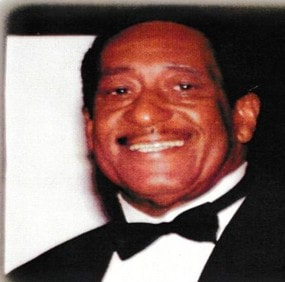

Bishop James N. Flowers, Jr.

Pastor, Singer, Songwriter and Best Dad Ever

Bishop James N. Flowers, Jr.

Pastor, Singer, Songwriter and Best Dad Ever

From a distance, a farewell to a ‘special humble, fair’ man

A drive-by memorial was held Monday for Bishop James N. Flowers Jr., a victim of covid-19, whose body was laid in repose in Seat Pleasant, Md. The city set up the memorial so people could pay their respects without exiting their vehicles. Flowers was the pastor of Shining Star Freewill Baptist Church for 38 years. (Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

By

Paul Duggan

April 14, 2020 at 12:15 p.m. EDT

It was a strange scene, but these are strange times, and the family of the late Bishop James N. Flowers Jr. knew his many friends would want to pay their respects. A wake in a funeral parlor was out of the question, so the pastor’s sons and daughters arranged for a drive-by viewing in a municipal parking lot.

“Do NOT get out of your vehicle,” the program said.

“Keep windows rolled up.”

Five weeks after Flowers preached what turned out to be his final sermon at Shining Star Freewill Baptist Church in Seat Pleasant, Md., and a week after he died of complications related to covid-19, the 84-year-old minister’s coffin was set on a bier under an open tent outside Seat Pleasant City Hall in Monday’s rain.

And for two hours, a procession of cars, trucks and SUVs snaked between traffic cones in the lot, the mourners slowing and staring out rain-streaked windows at the closed coffin as attendants with umbrellas waved them along.

“Walkers are NOT permitted,” said the program.

“Please wear a mask.”

Gospel music thumped from a sound system. An honor guard, two police officers in white masks, flanked the casket, which was covered in transparent plastic. Rain fell in sheets, then let up, then poured again, and the mourners kept rolling past.

Another homegoing in this pandemic spring.

The coronavirus death toll in Maryland, Virginia and the District was nearing 500 on Monday as dozens of motorists bid farewell to one of the victims, a reverend who founded a house of worship in a vacant auto garage in 1982 and, in 38 years, built it into a handsome brick church with about 200 congregants.

“My dad was just a special, humble, fair, caring man of God,” Linda Flowers, 52, said by phone before the viewing.

“Oh, he wasn’t always a servant of the Lord,” her brother Randy Flowers, 59, said on the same call.

“No, he wasn’t,” Linda Flowers said, laughing. He was a rock-and-roller back in the day.

He was a drinking man, too.

He was born in tiny Longwood, N.C., 50 miles from Wilmington, in 1936, a younger brother of Phil Flowers, a recording artist of modest renown in the 1950s and ’60s who started his career in the District and was a popular nightclub singer in the city for years.

Phil Flowers, who died in 2001, wrote hundreds of rock, blues and gospel tunes. Glen Campbell recorded a version of his song “I May Never Pass This Way Again.” He performed at the White House when Lyndon B. Johnson was president, and he toured with his siblings, including James Flowers, singing backup.

By

Paul Duggan

April 14, 2020 at 12:15 p.m. EDT

It was a strange scene, but these are strange times, and the family of the late Bishop James N. Flowers Jr. knew his many friends would want to pay their respects. A wake in a funeral parlor was out of the question, so the pastor’s sons and daughters arranged for a drive-by viewing in a municipal parking lot.

“Do NOT get out of your vehicle,” the program said.

“Keep windows rolled up.”

Five weeks after Flowers preached what turned out to be his final sermon at Shining Star Freewill Baptist Church in Seat Pleasant, Md., and a week after he died of complications related to covid-19, the 84-year-old minister’s coffin was set on a bier under an open tent outside Seat Pleasant City Hall in Monday’s rain.

And for two hours, a procession of cars, trucks and SUVs snaked between traffic cones in the lot, the mourners slowing and staring out rain-streaked windows at the closed coffin as attendants with umbrellas waved them along.

“Walkers are NOT permitted,” said the program.

“Please wear a mask.”

Gospel music thumped from a sound system. An honor guard, two police officers in white masks, flanked the casket, which was covered in transparent plastic. Rain fell in sheets, then let up, then poured again, and the mourners kept rolling past.

Another homegoing in this pandemic spring.

The coronavirus death toll in Maryland, Virginia and the District was nearing 500 on Monday as dozens of motorists bid farewell to one of the victims, a reverend who founded a house of worship in a vacant auto garage in 1982 and, in 38 years, built it into a handsome brick church with about 200 congregants.

“My dad was just a special, humble, fair, caring man of God,” Linda Flowers, 52, said by phone before the viewing.

“Oh, he wasn’t always a servant of the Lord,” her brother Randy Flowers, 59, said on the same call.

“No, he wasn’t,” Linda Flowers said, laughing. He was a rock-and-roller back in the day.

He was a drinking man, too.

He was born in tiny Longwood, N.C., 50 miles from Wilmington, in 1936, a younger brother of Phil Flowers, a recording artist of modest renown in the 1950s and ’60s who started his career in the District and was a popular nightclub singer in the city for years.

Phil Flowers, who died in 2001, wrote hundreds of rock, blues and gospel tunes. Glen Campbell recorded a version of his song “I May Never Pass This Way Again.” He performed at the White House when Lyndon B. Johnson was president, and he toured with his siblings, including James Flowers, singing backup.

Flowers and his wife, Margaret, before her death in 2019, in front of the Shining Star Freewill Baptist Church in Seat Pleasant, Md. (Courtesy of Linda Flowers)

James Flowers formed a band of his own in the late 1950s. He was the lead singer and was getting to be big on the D.C. club circuit. “You know how they get groupies that follow them around?” Randy Flowers said. One of his father’s groupies was a young woman named Margaret Chelednik, from a well-to-do family in Pennsylvania. She drove a Chevy Corvette and enjoyed the nightlife.

She heard him sing “Kansas City,” the story goes, and she fell for him right then, but there was a slight problem. Unlike Flowers, Chelednik was white.

Their firstborn, Randy, arrived in February 1961, four months before they became husband and wife in the District, back when such a union was scandalous to many people.

In fact, just across the Potomac River in Virginia, interracial marriage was still illegal.

“Mama’s family cut her off, disowned her, from when they started dating,” Randy Flowers said. Her brothers even came down from Pennsylvania and repossessed the Corvette her father had given her. “She loved my dad, though,” he said, and their marriage would span decades, until her death last spring.

James Flowers formed a band of his own in the late 1950s. He was the lead singer and was getting to be big on the D.C. club circuit. “You know how they get groupies that follow them around?” Randy Flowers said. One of his father’s groupies was a young woman named Margaret Chelednik, from a well-to-do family in Pennsylvania. She drove a Chevy Corvette and enjoyed the nightlife.

She heard him sing “Kansas City,” the story goes, and she fell for him right then, but there was a slight problem. Unlike Flowers, Chelednik was white.

Their firstborn, Randy, arrived in February 1961, four months before they became husband and wife in the District, back when such a union was scandalous to many people.

In fact, just across the Potomac River in Virginia, interracial marriage was still illegal.

“Mama’s family cut her off, disowned her, from when they started dating,” Randy Flowers said. Her brothers even came down from Pennsylvania and repossessed the Corvette her father had given her. “She loved my dad, though,” he said, and their marriage would span decades, until her death last spring.

Flowers, a rock singer in the Washington area during the 1950s and 1960s, and his wife, Margaret, at their wedding in June 1961. (Courtesy of Linda Flowers)

Not many years after the wedding, James Flowers experienced an epiphany.

“He was doing a show at the Howard Theatre,” Randy Flowers said. “Redd Foxx was the headliner. My dad’s band was opening for Redd Foxx — like I say, Dad was on the upswing. People said he was a rising star. But God had something different in mind.

“What had happened was, after they finished their first set, Dad went into the dressing room,” he said. “He started right in on his fifth of Johnnie Walker, and while he was drinking, he said, he started losing his breath. He said he couldn’t breathe.

“He said the Lord spoke to him. The Lord said: ‘You go onstage again, you’ll die. You leave now, you’ll live.’ He said he got his breath back, and he looked around at everybody. He said, ‘I’m gone,’ and he walked out — left my mother sitting in the theater.

“Now, this is him telling us the story. He walked around D.C., drunk, and ended up on East Capitol Street,” Randy Flowers continued. “His Cadillac was still parked at the theater. And he walked through the streets, he said, until he heard gospel music from a church.

“He said he walked up these steps, and a little white preacher was listening to gospel music, and the little white preacher said, ‘The Lord spoke to you tonight, didn’t he?’ Just like that. And hearing that, that’s what did it for him.”

Linda Flowers said, “That’s how Dad ended up following rock-and-roll to ‘Rock of Ages.’ ”

He quit the clubs for a quiet life.

He learned to fix watches and worked in a jewelry store for years. And he took to churchgoing.

On the website of Shining Star Freewill Baptist Church, the biography of Bishop Flowers mentions nothing about “Kansas City” or Sister Margaret’s Corvette or that night in the theater when he forsook Johnnie Walker for the Almighty.

It picks up the story later.

“On Wednesday, July 15, 1982, the first prayer service was held,” the website says. This was after Flowers and several co-founders had established their house of worship in the vacant garage. Flowers “used a paint can as his pulpit. There were 17 people in attendance that night.” From then on, he poured his soul into the place. In 1988, “Rev. Flowers organized the program ‘Families Against Drugs’ to combat the crime and drug problems which plagued the community,” the website says.

Randy Flowers said: “The drug scene got really bad around the church, and he was threatened. They’d say, ‘What color casket you want to have?’ He’d tell them, ‘Red, for the blood of Jesus.’ But even through all of that, some of the drug boys would at least talk to him. They’d listen to him a little bit.”

Over the years, “as the church grew spiritually, financially, and in membership, new renovations were undertaken,” the history says. Up went steepled brick walls. The sanctuary was expanded, rooms were added, a baptism pool was installed.

The church, in the 5700 block of Martin Luther King Jr. Highway, stands today as a monument to the bishop’s faith, his family said.

In early March, he came down with flu-like symptoms. He had no underlying health problems.

Linda Flowers, with whom he lived in Fort Washington, Md., took him to a hospital. He was tested for the novel coronavirus, which causes the disease covid-19, and sent home to await the result.

The test was inconclusive, his daughter said.

Then, on March 24, “he was having trouble breathing,” she said, “and he had a fever.”

A relative drove him to a different hospital, Inova Mount Vernon, in Alexandria, Va., where he was admitted. He was tested again for the coronavirus. The result came back positive.

Two weeks later, on April 6, he died. He is survived by two daughters and two sons, 11 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

After Monday morning’s outdoor wake in the rain, a hearse pulled up to the tent and carried the bishop’s coffin to National Harmony cemetery in Landover, Md. There, his closest loved ones gathered by the grave, while others looked on from cars, trucks and SUVs.

“Participants may NOT interact physically with clergy, family members, staff, or participants in other vehicles,” the program said.

They watched as he was laid to rest next to his wife of 58 years.

Not many years after the wedding, James Flowers experienced an epiphany.

“He was doing a show at the Howard Theatre,” Randy Flowers said. “Redd Foxx was the headliner. My dad’s band was opening for Redd Foxx — like I say, Dad was on the upswing. People said he was a rising star. But God had something different in mind.

“What had happened was, after they finished their first set, Dad went into the dressing room,” he said. “He started right in on his fifth of Johnnie Walker, and while he was drinking, he said, he started losing his breath. He said he couldn’t breathe.

“He said the Lord spoke to him. The Lord said: ‘You go onstage again, you’ll die. You leave now, you’ll live.’ He said he got his breath back, and he looked around at everybody. He said, ‘I’m gone,’ and he walked out — left my mother sitting in the theater.

“Now, this is him telling us the story. He walked around D.C., drunk, and ended up on East Capitol Street,” Randy Flowers continued. “His Cadillac was still parked at the theater. And he walked through the streets, he said, until he heard gospel music from a church.

“He said he walked up these steps, and a little white preacher was listening to gospel music, and the little white preacher said, ‘The Lord spoke to you tonight, didn’t he?’ Just like that. And hearing that, that’s what did it for him.”

Linda Flowers said, “That’s how Dad ended up following rock-and-roll to ‘Rock of Ages.’ ”

He quit the clubs for a quiet life.

He learned to fix watches and worked in a jewelry store for years. And he took to churchgoing.

On the website of Shining Star Freewill Baptist Church, the biography of Bishop Flowers mentions nothing about “Kansas City” or Sister Margaret’s Corvette or that night in the theater when he forsook Johnnie Walker for the Almighty.

It picks up the story later.

“On Wednesday, July 15, 1982, the first prayer service was held,” the website says. This was after Flowers and several co-founders had established their house of worship in the vacant garage. Flowers “used a paint can as his pulpit. There were 17 people in attendance that night.” From then on, he poured his soul into the place. In 1988, “Rev. Flowers organized the program ‘Families Against Drugs’ to combat the crime and drug problems which plagued the community,” the website says.

Randy Flowers said: “The drug scene got really bad around the church, and he was threatened. They’d say, ‘What color casket you want to have?’ He’d tell them, ‘Red, for the blood of Jesus.’ But even through all of that, some of the drug boys would at least talk to him. They’d listen to him a little bit.”

Over the years, “as the church grew spiritually, financially, and in membership, new renovations were undertaken,” the history says. Up went steepled brick walls. The sanctuary was expanded, rooms were added, a baptism pool was installed.

The church, in the 5700 block of Martin Luther King Jr. Highway, stands today as a monument to the bishop’s faith, his family said.

In early March, he came down with flu-like symptoms. He had no underlying health problems.

Linda Flowers, with whom he lived in Fort Washington, Md., took him to a hospital. He was tested for the novel coronavirus, which causes the disease covid-19, and sent home to await the result.

The test was inconclusive, his daughter said.

Then, on March 24, “he was having trouble breathing,” she said, “and he had a fever.”

A relative drove him to a different hospital, Inova Mount Vernon, in Alexandria, Va., where he was admitted. He was tested again for the coronavirus. The result came back positive.

Two weeks later, on April 6, he died. He is survived by two daughters and two sons, 11 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

After Monday morning’s outdoor wake in the rain, a hearse pulled up to the tent and carried the bishop’s coffin to National Harmony cemetery in Landover, Md. There, his closest loved ones gathered by the grave, while others looked on from cars, trucks and SUVs.

“Participants may NOT interact physically with clergy, family members, staff, or participants in other vehicles,” the program said.

They watched as he was laid to rest next to his wife of 58 years.

Memories Light the Corner of my Mind, Misty Water Colored Memories of the Way We Were